Rich siegel, z"l

Remarks by Barry Holtz

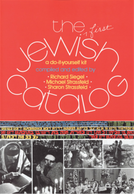

Richard Siegel passed away in Los Angeles, after two years fighting cancer, just two weeks before his 71st birthday. Rich joined the Havurah in its second year, after graduating from Brandeis. He received a Masters degree in the program then known as Contemporary Jewish Studies (later it became the Hornstein Program). It was there that under the supervision of Professor Joseph Lukinsky, z”l, (one of the founders of Havurat Shalom) he and fellow Havurah member George Savran wrote a joint Masters thesis called “A Proposal for a Jewish Whole Earth Catalog.” Shortly afterward Rich, Michael Strassfeld and Sharon Strassfeld realized this proposal by turning it into the best-selling and iconic book of the Jewish “Counter Culture” of the ‘60s and 70s,The Jewish Catalog.

Later on Rich led the National Foundation for Jewish Culture in New York for many years, as it supported both Jewish scholarship and the arts. He was one of the founding members of Minyan Maat, a truly innovative thinker about Jewish life and Jewish culture, a gifted shaliah tzibbur, a friend to many of us. Rich died surrounded by his wife Rabbi Laura Geller and his two (grown) children Andy and Ruthie. When Rich married Laura he left New York and moved to Los Angeles where she was the rabbi of a congregation. After a while he was asked to become the head of Hebrew Union College’s School of Jewish Non Profit Management which he did with great success, culminating in helping to secure a naming donation for the School.

During the past year Rich and his wife Laura were working on a fascinating project in Los Angeles about creating communities that dealt in creative ways with an aging Jewish population. Their book about this work was close to completion and will no doubt appear within the next short while. As ill as Rich was, it mattered greatly to him to attend the 50th anniversary reunion of Havurat Shalom, and with a great show of willpower despite being in considerable pain, he was able to be with us over Memorial Day weekend 2018 and to speak at the panel on aging. It was in essence a chance for him to say good-bye, though none of us expected that his end was so near. Yehi zikhro varukh.

Later on Rich led the National Foundation for Jewish Culture in New York for many years, as it supported both Jewish scholarship and the arts. He was one of the founding members of Minyan Maat, a truly innovative thinker about Jewish life and Jewish culture, a gifted shaliah tzibbur, a friend to many of us. Rich died surrounded by his wife Rabbi Laura Geller and his two (grown) children Andy and Ruthie. When Rich married Laura he left New York and moved to Los Angeles where she was the rabbi of a congregation. After a while he was asked to become the head of Hebrew Union College’s School of Jewish Non Profit Management which he did with great success, culminating in helping to secure a naming donation for the School.

During the past year Rich and his wife Laura were working on a fascinating project in Los Angeles about creating communities that dealt in creative ways with an aging Jewish population. Their book about this work was close to completion and will no doubt appear within the next short while. As ill as Rich was, it mattered greatly to him to attend the 50th anniversary reunion of Havurat Shalom, and with a great show of willpower despite being in considerable pain, he was able to be with us over Memorial Day weekend 2018 and to speak at the panel on aging. It was in essence a chance for him to say good-bye, though none of us expected that his end was so near. Yehi zikhro varukh.

Shaul Magid's article about Rich Seigel in Tablet

Rich coauthored Getting Good at Getting Older and edited The First Jewish Catalog.

DEAR RICHIE

Or: Counterculture Prose-Poem 2.0

by Joel Rosenberg

1. The name

To me, dear Rich will always be dear Richie,

just as our Bauhaus of the Jewish avant-garde

has long been known as “Havurat Shalom.”

Both house and Richie, both man and haverim,

are one—and at one inexorably with THE ONE.

What emanates from there still animates

the world, our innovation ever continues,

no small thanks to him. Branches, leaves,

rivers, and garments are some of the names

we use to spell diversity within the One,

and our dear Richie was a maestro of the art

of unifying past with future, and Oneness

with the variegated richness (or is it Richieness?)

of human Experience and the World.

2. The photo

A Brownie-camera photo (now lost) I took

of Richie on a sunny, springtime morning back

in 1971 (the day I flew to Santa Cruz for grad school),

shows him in the backyard at 113 College Ave.,

cradling in his arms the critter we called

Krishna Kat (whom I preferred to call,

The Kid), now famous to the world

amid the dedication of a then still-nascent book

I would eventually call The Jewish Cat. Here

in the snapshot, Krishna’s tail drapes down

from Richie’s arms, exactly parallel to him,

pointing directly to the ground, to the Whole

Earth ground that Richie tilled and shared

worldwide. And here was Richie:

tall, thin, and handsome—wearing then,

as I recall it, long hair and beard—suggesting,

in his bearing, traits I’d always associate

with him: calmness, dignity, unflappability,

rationality, compassion, a union of the

head and heart, an elegance of personhood

ideally suited to the nurturing of peoplehood.

3. The spirit of the era

I’m writing my reflections on Tisha b’Av,

to me the ideal day to register a sense

of loss and mark the irretrievable. I’m

sitting in a villa near the Dordogne, in France.

Carol and I arrived here from Portugal

and Catalonia, where stories abound

about the Spanish Inquisition and, among

us Jews, the “third Tisha b’Av”—that of

the Jews’ Expulsion.

The authoritarian mind

was rampant there, and it persisted later

in the fascism of Salazar and Franco.

These days, however, on balconies

in Catalonia are draped the flags

proclaiming independence: red-and-

yellow-striped, with a white star on

a triangle of blue, and on the walls,

the mottoes in Catalan: “Libertat!”

and “Democracia!”

In America, from 1932 till 1968,

we had the blessings of an open society:

narrowing the gap between the wealthy

and the poor. Republicans who sometimes

acted like Democrats. A gradual loosening

of social taboos. The Age of Aquarius

and what we then had called Free Love.

And so, both men and women, but

especially we men, had often jumped

with ease (or, arguably, too much ease)

from bed to bed. And in that spirit,

and wholly lacking any ill-intent,

Richie and I—some once or twice, though

not at the same time—were blessed with

the same woman’s love, or short liaison. They’ve

remained for me, back then, today, and always,

salt of the earth, a source of wisdom and

humanity, as is, today for 18 years, my own

beloved one. Berukhah ha-XX chromosome!

Without it in my life, and without her,

I would have been long gone.

And so the year 1968 poured forth

its hopes into what soon became a far

less gentle Age. Among the Jewish

counterculture, there was still much

to keep us occupied—prayer, and poetry,

and meditation, Hebrew calligraphy,

divrey Torah, and other Jewish arts.

Works of imagination and academic

scholarship. The music of Carlebach

and Dylan, the Beatles and the Stones,

the sounds of zemirot and niggunim.

Life leavened by cannabis and psychedelics.

And later, in the tents of prayer, egalitarian

minyans, some with neutrally or androgynously

gendered siddurim. Movements for social change,

and racial justice: for end of war in Southeast Asia,

for peace between the Jews and Arabs at

the juncture of three continents. Some

500,000 of us (including much of Havurat

Shalom) had turned out in Washington. D. C.,

in November, 1969, attempting to persuade

Dick Nixon not to bomb the millions.

in Vietnam and its surrounding nations,

just for the sake of staying in office.

But conscience no longer ruled our

leadership. The Tree of Life was turned

into the Tree of Knowledge.

Shekhinah still had far to travel,

as, e’er further-on-steroids, is still

the case today.

But Jewish counterculture still throve

and thrives. And Richie was the fount of much

that happened. He turned “Counterculture”

into Culture, and “National Foundation”

into Foundation. Calmness and dignity,

innovation, hope, and aspiration

were still the lodestone for what by then

had now become a Havurah diaspora.

And, as it were, “havuratility” still grows

throughout the global Jewish realm.

And What Surrounds and Fills all Worlds

dwells in our hearts and guides our steps.

4. Dear Richie

And so, “dear Richie,” in an adjectival sense,

will now become “Dear Richie,” as a letter sent

from me to you. I want to pour into it all

my gratitude for a friendship that, however much

it mostly had extended over short visits between

Cambridge and Port Washington, between

Somerville and Manhattan’s Upper West Side,

for me was ever a source of nourishment and

validation. And while we never quite were

soulmates, you always made me feel included

as a friend and artistic collaborator, if only in

our being among the eldest generation

that came in, in ‘sixty-eight and ‘sixty-nine,

and I gave back to you the writing you encouraged:

my first piece for The Jewish Catalog, and in my

year of unemployment between Wesleyan

and Tufts, you hired me to write entries

for The Jewish Almanac. Those tasks were fun,

and in my article on the Hebrew alphabet

I set forth a theory I have always hoped

to reshape into scholarship—arguing,

namely, that in the earliest Semitic alphabets

(resembling our Latin alphabet) were diagrams

of lips, mouth, teeth, tongue, and throat,

and flows of breath, which uttered all the

sounds of speech. It liberated writing

from hieroglyphs and cuneiform, from

its monopoly by priests and scribes.

One of the greatest human revolutions,

thus democratizing writing and fostering

literacy, and the plea for it, embodied

in our Torah and Tanakh.

There’s more—a host

of Jewish arts events that you created,

out in Stony Brook and in Manhattan,

yielding writing revenue for me, and lore

that I could celebrate. You almost introduced

me to the great Bashevis Singer, had rush-

hour Triborough traffic not impeded me from

heading out to you upon Long Island. (I later

met him in the company of Dovid R.)

In all the things

that you’ve conceived and run, you put Jewish arts,

and avant-garde, and quiet, humming revolution

on the map of Jewish life.

5. My grief, which we all share

I grieve for you, my friend,

not just because you’ve left us, nor just

because of things I never got to say,

but because, in your departure, you passed

through so much grievous suffering. Would that

every pang or stab of pain, or nausea,

or false certainty and rude awakening,

or sense of a divine abandonment

had been instead the sure and steady

motions of a sound and permanent

remission. And I pray that in

whatever afterlife we all, sooner or

later, might have yet to undergo,

you are enjoying the blisses

of Gan Eden, and are

sheltered in the wings

of the Shekhinah.

May all that I have said,

and each of us, in all

our separate elegies for you,

combine into a single and

eternal Love.

Begun on Tisha b’Av 5778,

and completed on

Tu b’Av, 5778

Or: Counterculture Prose-Poem 2.0

by Joel Rosenberg

1. The name

To me, dear Rich will always be dear Richie,

just as our Bauhaus of the Jewish avant-garde

has long been known as “Havurat Shalom.”

Both house and Richie, both man and haverim,

are one—and at one inexorably with THE ONE.

What emanates from there still animates

the world, our innovation ever continues,

no small thanks to him. Branches, leaves,

rivers, and garments are some of the names

we use to spell diversity within the One,

and our dear Richie was a maestro of the art

of unifying past with future, and Oneness

with the variegated richness (or is it Richieness?)

of human Experience and the World.

2. The photo

A Brownie-camera photo (now lost) I took

of Richie on a sunny, springtime morning back

in 1971 (the day I flew to Santa Cruz for grad school),

shows him in the backyard at 113 College Ave.,

cradling in his arms the critter we called

Krishna Kat (whom I preferred to call,

The Kid), now famous to the world

amid the dedication of a then still-nascent book

I would eventually call The Jewish Cat. Here

in the snapshot, Krishna’s tail drapes down

from Richie’s arms, exactly parallel to him,

pointing directly to the ground, to the Whole

Earth ground that Richie tilled and shared

worldwide. And here was Richie:

tall, thin, and handsome—wearing then,

as I recall it, long hair and beard—suggesting,

in his bearing, traits I’d always associate

with him: calmness, dignity, unflappability,

rationality, compassion, a union of the

head and heart, an elegance of personhood

ideally suited to the nurturing of peoplehood.

3. The spirit of the era

I’m writing my reflections on Tisha b’Av,

to me the ideal day to register a sense

of loss and mark the irretrievable. I’m

sitting in a villa near the Dordogne, in France.

Carol and I arrived here from Portugal

and Catalonia, where stories abound

about the Spanish Inquisition and, among

us Jews, the “third Tisha b’Av”—that of

the Jews’ Expulsion.

The authoritarian mind

was rampant there, and it persisted later

in the fascism of Salazar and Franco.

These days, however, on balconies

in Catalonia are draped the flags

proclaiming independence: red-and-

yellow-striped, with a white star on

a triangle of blue, and on the walls,

the mottoes in Catalan: “Libertat!”

and “Democracia!”

In America, from 1932 till 1968,

we had the blessings of an open society:

narrowing the gap between the wealthy

and the poor. Republicans who sometimes

acted like Democrats. A gradual loosening

of social taboos. The Age of Aquarius

and what we then had called Free Love.

And so, both men and women, but

especially we men, had often jumped

with ease (or, arguably, too much ease)

from bed to bed. And in that spirit,

and wholly lacking any ill-intent,

Richie and I—some once or twice, though

not at the same time—were blessed with

the same woman’s love, or short liaison. They’ve

remained for me, back then, today, and always,

salt of the earth, a source of wisdom and

humanity, as is, today for 18 years, my own

beloved one. Berukhah ha-XX chromosome!

Without it in my life, and without her,

I would have been long gone.

And so the year 1968 poured forth

its hopes into what soon became a far

less gentle Age. Among the Jewish

counterculture, there was still much

to keep us occupied—prayer, and poetry,

and meditation, Hebrew calligraphy,

divrey Torah, and other Jewish arts.

Works of imagination and academic

scholarship. The music of Carlebach

and Dylan, the Beatles and the Stones,

the sounds of zemirot and niggunim.

Life leavened by cannabis and psychedelics.

And later, in the tents of prayer, egalitarian

minyans, some with neutrally or androgynously

gendered siddurim. Movements for social change,

and racial justice: for end of war in Southeast Asia,

for peace between the Jews and Arabs at

the juncture of three continents. Some

500,000 of us (including much of Havurat

Shalom) had turned out in Washington. D. C.,

in November, 1969, attempting to persuade

Dick Nixon not to bomb the millions.

in Vietnam and its surrounding nations,

just for the sake of staying in office.

But conscience no longer ruled our

leadership. The Tree of Life was turned

into the Tree of Knowledge.

Shekhinah still had far to travel,

as, e’er further-on-steroids, is still

the case today.

But Jewish counterculture still throve

and thrives. And Richie was the fount of much

that happened. He turned “Counterculture”

into Culture, and “National Foundation”

into Foundation. Calmness and dignity,

innovation, hope, and aspiration

were still the lodestone for what by then

had now become a Havurah diaspora.

And, as it were, “havuratility” still grows

throughout the global Jewish realm.

And What Surrounds and Fills all Worlds

dwells in our hearts and guides our steps.

4. Dear Richie

And so, “dear Richie,” in an adjectival sense,

will now become “Dear Richie,” as a letter sent

from me to you. I want to pour into it all

my gratitude for a friendship that, however much

it mostly had extended over short visits between

Cambridge and Port Washington, between

Somerville and Manhattan’s Upper West Side,

for me was ever a source of nourishment and

validation. And while we never quite were

soulmates, you always made me feel included

as a friend and artistic collaborator, if only in

our being among the eldest generation

that came in, in ‘sixty-eight and ‘sixty-nine,

and I gave back to you the writing you encouraged:

my first piece for The Jewish Catalog, and in my

year of unemployment between Wesleyan

and Tufts, you hired me to write entries

for The Jewish Almanac. Those tasks were fun,

and in my article on the Hebrew alphabet

I set forth a theory I have always hoped

to reshape into scholarship—arguing,

namely, that in the earliest Semitic alphabets

(resembling our Latin alphabet) were diagrams

of lips, mouth, teeth, tongue, and throat,

and flows of breath, which uttered all the

sounds of speech. It liberated writing

from hieroglyphs and cuneiform, from

its monopoly by priests and scribes.

One of the greatest human revolutions,

thus democratizing writing and fostering

literacy, and the plea for it, embodied

in our Torah and Tanakh.

There’s more—a host

of Jewish arts events that you created,

out in Stony Brook and in Manhattan,

yielding writing revenue for me, and lore

that I could celebrate. You almost introduced

me to the great Bashevis Singer, had rush-

hour Triborough traffic not impeded me from

heading out to you upon Long Island. (I later

met him in the company of Dovid R.)

In all the things

that you’ve conceived and run, you put Jewish arts,

and avant-garde, and quiet, humming revolution

on the map of Jewish life.

5. My grief, which we all share

I grieve for you, my friend,

not just because you’ve left us, nor just

because of things I never got to say,

but because, in your departure, you passed

through so much grievous suffering. Would that

every pang or stab of pain, or nausea,

or false certainty and rude awakening,

or sense of a divine abandonment

had been instead the sure and steady

motions of a sound and permanent

remission. And I pray that in

whatever afterlife we all, sooner or

later, might have yet to undergo,

you are enjoying the blisses

of Gan Eden, and are

sheltered in the wings

of the Shekhinah.

May all that I have said,

and each of us, in all

our separate elegies for you,

combine into a single and

eternal Love.

Begun on Tisha b’Av 5778,

and completed on

Tu b’Av, 5778