I’m offering these observations in safety, sheltered and far away from the horrible things done by Hamas and the horrible things being done by Israel. And I can’t imagine that any Israeli or Palestinian is impatiently waiting to hear a pacifist’s perspective on what’s going on, the needs of the hour are so intense. If I offer that perspective nonetheless, it’s not only because Phil invited me – not the least challenging invitation I’ve ever received, so among the invitations I’m most grateful for – but also because in the world we live in, conducting the war on war feels crucial, and because pacifists who want a world without war need to imagine how they would run it. (George Orwell wrote that pacifists who could not imagine being in power were not serious.)

And also because it is so awful to read of what the Israeli army is doing in Gaza, what Israeli settlers are doing in the West Bank, of what Israeli journalists and ministers of state are saying to dehumanize Gazans in particular and Palestinians in general, to read and hear and to feel isolated, powerless, silent, and because any occasion for speaking out to or speaking with friends or colleagues or just fellow passengers to the grave is so precious, so much a deliverance from the deadening passivity we risk being condemned to. Thank you, thank you.

Prefatory

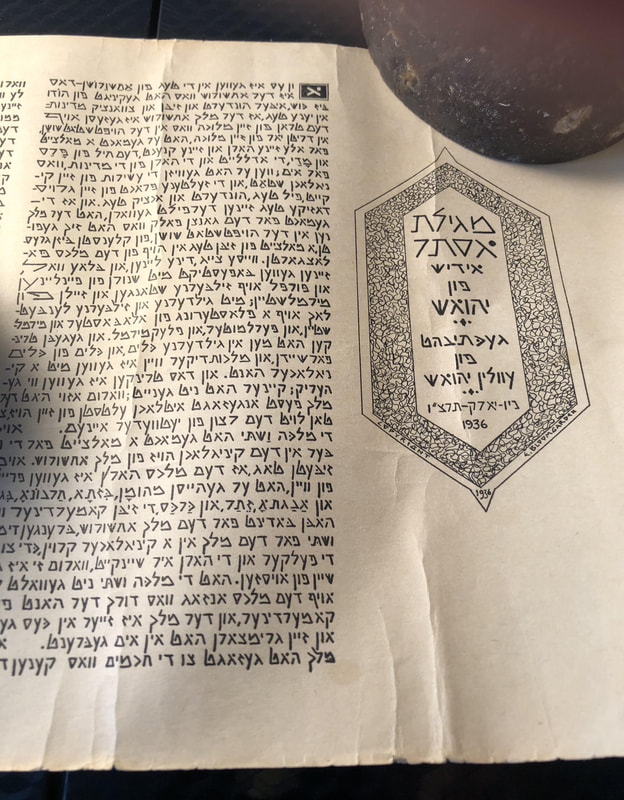

1) “Seek peace and pursue it, ”bakesh shalom v’rodfehu. I take my title from that verse in psalm 34 because I want to make clear that the pursuit of peace, which I take to be the task of the pacifist – and not just maintaining a preference of peace over war - is as much a part of Jewish tradition as is the annihilation of Amalek, which has been more in the news. That is made clear by this verse in particular, because it does something unusual, namely, provide two verbs for one object: don’t just seek peace, pursue it – zukh sholem un yog zikh nokh im, in Yehoyesh’s Yiddish translation of the verse. Commentators love doublings, and there’s a passage in the minor Talmudic tractate called perek hashalom, the chapter of peace, that comments on that trait in this verse:

Hezekiah said: Great is peace, for in connection with all other precepts in the Torah it is written, If thou see, etc., If thou meet, If there chance, If thou buildest, [implying,] if a precept comes to your hand, you are bound to perform it; *But if not, you are not bound to perform it. But what is written in connection with peace? Seek peace, and pursue it, [meaning,] seek it in your place and follow it to another place *if your presence can help to bring about peace there.

Do not, that is, make your pursuit of peace conditional, contingent; pursue it always and everywhere.

Another passage from that same tractate:

R. Jose the Galilean said: Great is peace, since even in a time of war one should begin [by attempting to arrange] peace, as it is stated, When thou drawest nigh unto a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace unto it. *Deut. 20, 10.

I’ll repeat that, or paraphrase it. When you approach a city to make war upon it, whether Sderot or Rafah, even then, especially then, propose peace to it. Start with that.

These aren’t the only pertinent passages in Jewish tradition – there’s a book on the subject, Evelyn Willcock’s Pacifism and the Jews - but they’re enough to establish the point at issue.

2) Lots of goodhearted people wish there were peace in the Middle East, wish that Hamas had not committed mass murder and would release its hostages, wish that the Israel Defense Forces were not killing and wounding and immiserating so many civilians in Gaza, so many children in particular, that the government of Israel would release all Palestinian political prisoners. But such wishes are not pacifism. Pacifism rejects the making of war across the board. Pacifists do not say, “I’m a pacifist but I support this war”; people who say that are not pacifists. Pacifists accept as a constraint on their wishes and schemes that those wishes and schemes will not include the making of war. Pacifists regard war the way Gandalf regards the One Ring: whatever you think you can do with it, however fair your visions of what you could accomplish, do not use it, you cannot control it, it will master and betray you. (Tolkien said of World War II, “they are winning the war with the Ring.”)

Pacifism requires a willingness to pay the price of that constraint. Whatever we wish for as pacifists, we have to figure out how to get without making war. Maybe we have to accept that some of the things that we wish for we can’t get at all, since it’s only through war that we could get them. (In the latter part of this talk I’ll be doing my best to imagine how we could get at least some of the things we wish for without war, but I’ll try to be honest about the limitations.)

3) As is probably clear, pacifists reject the idea of just war – which was, as pacifists know but others may not, developed in the West by St. Augustine as a means to make it possible for Christians, who were then pacifists, to support the wars of the state. Pacifists also reject the idea of humane war; on this see Samuel Moyn’s recent lacerating book Humane.

4) As is probably also clear, but is indispensable to say, pacifists reject the movement slogan, “no justice, no peace.” I’ve been at demonstrations where that slogan was chanted, and no doubt I’ve chanted it myself. But I reject it. Peace without justice – what scholars in peace studies, following Johan Galtung and Martin Luther King, call negative peace – is worse than peace with justice. But it is still peace. In a state of negative peace, if you are a kid you can get up in the morning, have breakfast, go to school, play with your friends. If you are a grownup you can go to work, buy flour for making bread, buy medicine for an illness, find a spare moment to sit with friends in a bar or a tearoom. And at night you can sleep, there will be no terrifying sounds in the night of bombs or shells or collapsing buildings – ve’lo yeshama od chamas b’artsam, “the sound of violence will no longer be heard in your land.” That is not nothing.

I quote from a theater piece called The Gaza Monologues, narrated by 33 young people in Gaza in 2010:

I dream of having ONE day of safety, I’m sure the world is too busy to remember our situation; six years have passed since we wrote our monologues and we are still under siege … When can we live in peace like the rest of the World? (https://www.gazamonologues.com)

That is a very modest demand: safety, peace. Not justice. But what it demands is a world away from what the speaker has.

5) Pacifisms are of many kinds. My own opposes war but not all violence, as I learned when I realized, listening to my students, that I could not condemn someone being raped for knifing their rapist. I am “serious” in Orwell’s sense, i.e., I want to imagine how to win, and also in King’s, i.e., I do not regard my position as sinless. (King’s account is in an essay called “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence.”) I allow a distinction between war and policing, as will become clear later, and a distinction between soldier and civilian. But I hold fast to the idea, principle, axiom, blessing, that we are all created b’tselem elohim, in the image of God, our enemies no less than we, soldiers no less than civilians, and I oppose war because it requires us to deny that principle, it in fact exalts that denial.

The War in Gaza

1) I’ll begin with something that’s predictable but necessary. A pacifist has to condemn both the Hamas attacks on October 7th and Israel’s war in Gaza, and both condemnations arise from the principle just stated. No claim that this is what decolonization looks like (in defense of the Hamas attacks), that this is what just war looks like (in defense of Israel’s war) matters more than that principle. For decolonizers and disciples (and in my view misreaders) of Frantz Fanon on the left, for recolonizers and ethnic cleansers and zealots of all kinds on the right, for all for whom the idealized end justifies the horrific means, these paired condemnations are bland and boring, too even-handed. I myself sometimes distrust even-handedness, it feels weak. But I hold to it here.

2) The American pacifist Kathy Kelly said that pacifists need to be concrete. When I read about the war in Gaza, I’m moved by what is concrete and repelled by what is abstract, this even before I discern the argument. Ted Deutch is the CEO of the American Jewish Committee, and said: “A premature cease-fire, without ensuring the elimination of Hamas’ military and governing capabilities, will only prolong that organization’s reign of terror over the people of Gaza, perpetuate its threat to the Israeli citizenry and doom any prospect of a political end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” I don’t agree with his claims; but even before I get to them I know that the abstractness of his language is veiling what is being done. Compare this statement by the Haaretz reporter Gideon Levy: “11,500 children have been killed in Gaza.” If Ted Deutsch were to say, “I believe that the slaughter of 11,500 children is justified,” I would oppose him – how on earth can that slaughter be justified? - but he would at least be defending what is actually happening. (That number is out of date; the current estimate is 13,000. That number will rise.)

3) There are deep desires at work right now, among the militants of Hamas and among the militants of Israel, and deep hopes. Each group dreams of eliminating the other, and of living in the other’s absence, in a utopia, whether that utopia is Israel sovereign and unchallenged from the river to the sea, or Israel wiped from the face of the earth. Both Hamas militants and Israeli zealots are utopians, what the historian Jay Winter calls “major utopians.” Winter distrusts major utopians, among whom are, for him, Stalin and Mao, possessed by what the political theorist Mathias Thaler calls “despotic reveries of social engineering.” So do I.

Pacifism, on the other hand, is a minor utopia, with smaller claims, as Winter implies and as Thaler says outright.

I remember a talk many years ago by the Israeli scholar Moshe Halbertal, at a moment in the history of Israel-Palestine that then seemed fraught with danger but which now seems idyllic, as pretty much anything would at the present moment, with so many children being killed daily. At that talk, Halbertal said that for people to make peace, they have to give up their dreams – i.e., the utopias I just mentioned – but that they can then be free of their nightmares.

As of the moment, both groups are unwilling to give up their dreams; they think they can bring them into being. Peace is for them second-best at best.

4) (This is the longest section of the talk.) What does a pacifist – what do I, that is – say should happen now? It’s in some way an unfair question, since it asks pacifists to weigh in at a moment that they would, had they had the power, have done everything possible to avert. Or as the Jewish American journalist Peter Beinart puts it, “it feels a little bit like someone has driven a car into a ditch and then is asking you how to get out of it.” But it can’t be right simply to refuse to answer, and in any case, presumably you’d want to help the driver get the car out of the ditch regardless of how they got there. So I’ll answer the question, within the constraints of pacifism – no war – and within the limits of what’s possible. (Within the limits, but not at some timid, safe distance from the limits, right up against them.)

I’ll hold to Beinart’s simile for a while. The first thing is to get the car out of the ditch. In the present context, that means getting to some sort of ceasefire, however long, however named, and to the release of some hostages. Towards that end, every strategy and tactic is of value. Successful campaigns against wars, like successful campaigns generally, are various. Radicals criticize moderates and vice-versa, but in the end both contribute. The campaign against Israel’s war is already as various as any. Among its modes of action: letters to American congresspeople, online petitions for ceasefire, municipal resolutions for ceasefire (three of them so far in my home state: Somerville, Cambridge, Medford, with resolutions moving forward in Amherst, Easthampton, Greenfield, and Northampton), blocking roads, blocking access to the Statue of Liberty (a former student of mine was there), self-immolation (on December 1st, in front of the Israeli consulate in Atlanta and now again on February 25th, in front of the Israeli consulate in Washington, D. C.), support of artists and writers being banned for supporting a ceasefire, refusal to pay taxes that fund American support of the Israeli military, displaying Palestinian flags, voting uncommitted, supporting journalists aiming to provide information to Israeli Jews about what is happening in Gaza. The South African charge of genocide brought against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

(I am aware that most of these measures are focused chiefly on influencing Israel, not at all or nowhere near as much on influencing Hamas, and that that cannot be right; a ceasefire requires two parties, Hamas was party to the first ceasefire and will be party to any ceasefire to come, it has agency. Whatever means there are of influencing it towards a ceasefire and the release of its hostages seem to me of value. But I do not know what they might be, not myself having any connection here that I might draw on to exercise influence, no legislator to vote for or campaign against, no addressee to whom to direct a letter. That is my limitation. Surely others could do more.)

Also of value are the ongoing negotiations themselves and the people taking part in them, the process and not only the result. Those people are citizens of minor utopias; they are diplomats by vocation or by function, who leave everyone unsatisfied but also undead. (Pacifists focused on non-direct action often disparage diplomats and governments, but they too have work to do. Pacifists have much in common with diplomats, actually, though neither group consistently recognizes this.)

When I read stories about negotiations between Israel and Hamas - not direct negotiations, to be sure, indirect at several removes, with the US and Qatar and Egypt and Israel and Hamas all involved, somehow communicating - I note that both Israel and Hamas are being described as rational entities. The sentences of the accounts somewhat resemble sentences describing unions and management during a strike. “The two sides are far apart,” “negotiations continue,” “Hamas stated its demands,” “Israel stated its demands,” “there is agreement on some matters but other matters remain unresolved” etc. Such sentences allow for a ceasefire; they may not lead to one, but they could. Sentences about Israelis as Nazis, or about Hamas as worse than the Nazis, whatever their truth value, cannot. Who negotiates with Nazis?

Nor are such sentences only sentences; in such negotiations, the two parties are behaving like rational entities, having meetings, using words (“use your words,” we say to children), delaying, compromising or not compromising. And should there be a ceasefire, as there was a while back, and may there be one again, there will be, during that ceasefire, some releasing of hostages, some release of prisoners, some holding to agreements and no doubt some failing to hold to agreements, and all of that behavior will be the behavior of non-monstrous entities, who can go on negotiating ceasefires until one of the ceasefires lasts.

A friend of mine said to me, “Okay, ceasefire, but what next?” A fair question. In one sense an easy question: end the Occupation, that being in my judgment the underlying cause of conflict. (I went to a Women in Black demonstration in Jerusalem, in 1992. All the women held identical small signs saying dai l’kibush, stop the Occupation. It was true then, it is true now.)

In another sense, a tragically hard question. No Israeli government in the foreseeable future will do anything of the kind. No Israeli government will do even the smaller, more intermediate things Peter Beinart thoughtfully sets out in the piece I borrowed the car-in-a-ditch simile from (Beinart admits as much): treat the murderous agents like criminals (“make law, not war,” as James Carroll wrote shortly after the attacks of September 11th, and no one did that either), release non-Hamas Palestinian prisoners, help put on Palestinian elections, accept the 1967 borderlines as the basis for a political settlement, re-admit Hamas to Palestinian political life if it observes a ceasefire and agrees to abide by decisions made by Palestinians in referendums. Whatever steps can be taken now are smaller still, more gradual and indirect and slow.

But getting to a ceasefire is not just okay. I am writing this sentence one day after the day on which, so far as I can tell, the Israeli army fired on a group of hungry Gazans trying to get their hands on food from some trucks. To be fair, the army spokesman called the group “a mob,” said the Gazans died in stampedes, said “this has nothing to do with Israel.” A Gazan witness said, “we went to get flour. The Israeli army shot at us.” An Al Jazeera reporter named Ismail al-Ghoul said that “after opening fire, Israeli tanks advanced and ran over many of the dead and injured bodies.” (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/29/dozens-killed-injured-by-israeli-fire-in-gaza-while-collecting-food-aid?s=08)

I admit the uncertainty. But I don’t in some way care. I’m with the Israeli journalist Dalia Scheindlin, who wrote, “As of this writing, at least 112 Palestinians are dead, over 700 wounded. Social media can battle out which side killed how many, but I know the truth: the war killed all of them. It has to stop.”

It has to stop, and ceasefire, being at least a partial stoppage, would be not just okay but a miracle.

Two final points and I’ll be done.

First: I’m old enough, and you are not, to have been in the former East Germany and the former Czechoslovakia, when the latter was a repressive Communist state and the latter a state under repressive Russian control. Those facts seemed immutable in 1970, when I was in East Germany, and in 1972, when I was in Czechoslovakia. But the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, and in that same year Václav Havel became the Czechoslovakian President. (My great aunt Hana Heitlingerova was his Hebrew translator, by the way). What we think is immutable might not be.

And second, some lines by Tracy Smith, from a poem called “Everybody’s Autobiography,” which I came across a week ago, and I’ll let them be my last word:

In a dream, my children

Glisten inside raindrops, or teardrops.

Like strangers, like seeds of children.

I will only be allowed to claim them

If I consent to love everyone’s children.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed