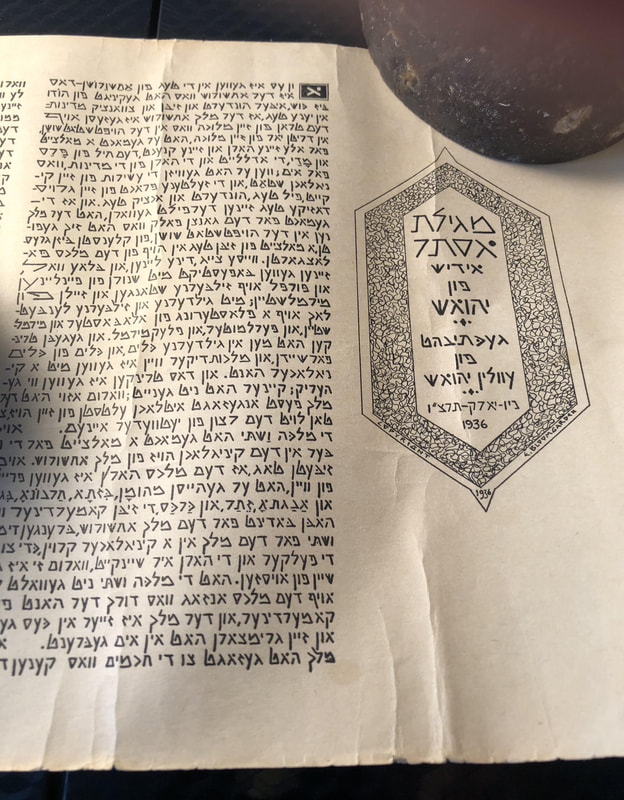

This is a story about a scroll, a scroll containing Yehoyesh’s Yiddish translation of the book of Esther, calligraphed by his daughter Evelyn, purchased by me, and in the end, once we’ve worked out insurance and storage questions, to be given by me to the Hav.

Here’s what happened. For some years now, on Purim at the Hav, I’ve been performing Yehoyesh’s translation of chapter 7 of the book of Esther, in a highly theatrical, exuberantly over-acted way, influenced by, though I think also independent of, Hav alum Dovid Roskies’s stunning recitation, in multiple voices and accents, of the whole megile, which can be found here. Which is why fellow Hav member Todd Kaplan told me he’d come across the Esther scroll on Craig’s List, and maybe I should take a look. And I did, and though I’m inclined these days to downsize rather than accumulate, I wrote the seller and said I’d like to buy the scroll.

Various events intervened between that moment and the moment of acquisition, but finally, on January 3rd, I met the seller outside a Roslindale coffee shop. He had brought the scroll in a featureless brown paper bag, and had asked to be paid in cash, which made everything feel eerie, as if I were committing a crime. I took the scroll out, had a look, saw that it was all there (and beautiful), paid the price.

It might have ended there, but it was an anomalously warm day, and the seller and I got to talking. How had he come by the scroll, I asked? He said it had been his father’s, and that he knew no more than that. His father and mother had spoken Yiddish to each other and to their parents, but not – this is a common Jewish American story – to their children. So he had not grown up with Yiddish, though his high school German had sometimes helped him speak with his grandparents. He said he wanted the scroll to go to a good recipient – “what there is shall go to them who are good for it,” as they say in Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle - and I told him I thought I was indeed a good recipient, and that his finding me, or Todd’s finding him and making the shidukh, or both, were bashert, destined, fated. Then he gave me two Yiddish theater bills as a gift, and headed off, and I headed into the coffee shop. A very nice man.

That might have been the end, but there’s this great Facebook page for Yiddishists, called yidforsh, and I asked there whether people knew things about the scroll. And of course they did! – pointing me to, among other places a terrific article in In geveb by Shifra Epstein, in which we read the following:

The Yehoash megile is completely unique in the history of megillot published in the United States; it is the only known megile scroll printed in Yiddish. The Yiddish megile follows the traditional design of a Hebrew illuminated scroll. Each of the book’s ten chapters begins with an enlarged letter set within an embellished rectangular frame. Each page is composed of two columns, with forty-two lines per column, according to the traditional scribal layout required for the writing of a Torah scroll. The scroll was also reproduced in printed book form in 1936.

I bought a copy of the megile scroll printed above in early 1978 from Zosa Szajkowski, YIVO’s archivist at the time,11 while conducting research for an exhibition at the YIVO archives: Purim: The Face and the Mask. In 1979 the exhibit, including the Yehoash megile, went up. Images of the scroll were also reproduced in the exhibition catalogue. After the exhibit was dismantled, I donated the megile to the Yeshiva University Museum, where it is currently part of the museum collection. The megile can also be found in the collection of the Jewish Theological Library and at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.

And there’s a fine article by Shulamith Berger on the Yeshiva University website, from which we learn that:

"Although the Yiddish megilah is printed on paper, and thus not kosher for ritual use on Purim, the library’s copy has creases in it, as if it had been folded in the traditional manner. Before the megilah is read in the synagogue on Purim, the scroll is folded to resemble a letter, in recognition of the igeret, the letter, which Esther and Mordecai sent to the Jews about commemorating Purim. Perhaps this Yiddish megilah served as a “people’s megilah,” a way for someone to participate in the experience of using a scroll while enjoying the mellifluous modern Yiddish translation rendered in spare, handsome lettering, evocative of the spirit of centuries of Jewish history and languages."

We are in good company, with the Yeshiva museum, the Jewish Theological Library, the National Library of Israel. And there are stories about the scroll not yet told, having to do with the daughter who did the calligraphy, the gendered character of the scroll, the experiences women have had, and are now having, of that holiday and of this translation. Not stories I can tell at the moment, but stories worth unearthing.

But I didn’t buy the scroll as something to classify and study and preserve, though those are fine things to do. I bought it because I hoped that at some point, in what I trust will be the long history of Havurat Shalom, someone will come along who would like to carry on this tradition, which was David Roskies before it was mine, and which will, I hope be someone else’s when it’s mine no longer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed